The Internet began as a U.S. military computer network meant to survive a nuclear attack. ARPANET, developed in the 1960's, stored information in a broad network of computers linked by distributed hubs so that an attack against one or more hubs could not bring down the entire thing.

Decentralized. Interconnected. Robust. Nuke-Proof.

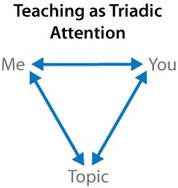

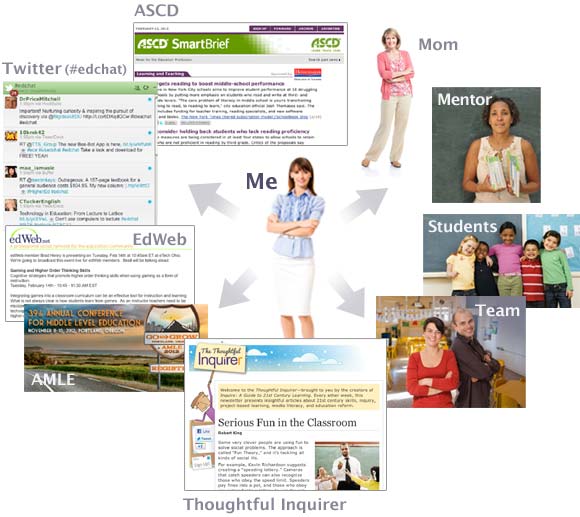

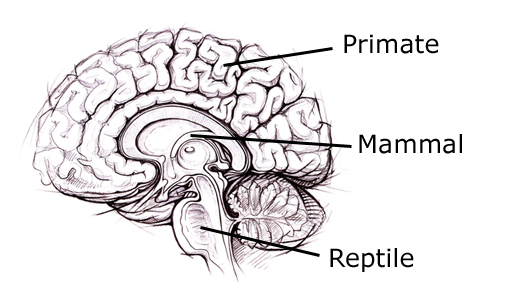

Wouldn't it be great if you could get your students to build the same kind of neural networks around the subjects you teach? How can you move beyond superficial, short-term learning to create learning that sticks? Modern brain science suggests one answer that you can apply in your classroom today.

Providing a Sensory Banquet

The key to creating robust neural networks in students' brains is to give them a rich sensory diet as they engage with material. Here's what Ronald Kotulak says in Inside the Brain:

The brain gobbles up its external environment in bites and chunks through its sensory system: vision, hearing, smell, touch, and taste. Then the digested world is reassembled in the form of trillions of connections between brain cells that are constantly growing or dying, or becoming stronger or weaker, depending upon the richness of the banquet.

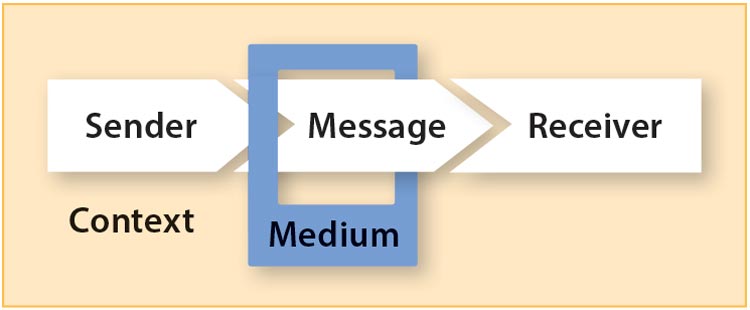

By engaging many different senses, you lay the information down through multiple interconnected neural pathways, placing it in long-term memory and making it robust and "nuke-proof."

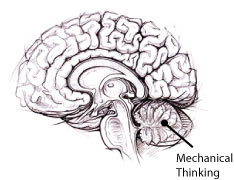

Map of the Reading Brain: Imagine that you ask your students to read a paragraph about the Treaty of Versailles. The information comes in through the eyes, imprints upon the retinas, and then travels through the optic nerves to the occipital lobe at the back of the brain. The information there is decoded into words, and impulses travel to the temporal lobes, where language processing occurs. The impulses then arc up to the frontal lobe meaning of the words is evaluated.

Read more